History

When CP Scott retired from managing and editing the paper in July 1929, he passed control to his two sons. John was manager and Edward (Ted) took over as editor.

The death of CP Scott in 1932 brought into sharp focus a very real threat to the future independence of the Guardian.

The Inland Revenue believed there was a case for imposing death duties. Neither CP Scott nor his sons had ever taken anything more than their modest salaries from the business. They were not rich men, and could not have afforded to pay the tax bill themselves. Payment by the business would have crippled it.

The Inland Revenue eventually accepted that death duties were not payable as ownership was split between CP Scott and his sons, and CP had therefore only been a minority shareholder.

Following CP’s death, ownership was shared between John and Ted. Should one of them die, the paper’s future would be jeopardised by the threat of death duties – and the predatory interest of competitors.

The crisis came sooner than expected. Just four months after his father’s death, Ted was killed in a boating accident on Lake Windermere.

The two brothers had agreed that if one died, the survivor would purchase all of the deceased’s shares at a nominal price. John was now the sole owner of the business, and he was convinced the Inland Revenue would claim full death duties in the event of his death. This would almost certainly mean the end of the Manchester Guardian as an independent liberal newspaper – the legacy of his father and the paper’s founder.

John Scott was acutely aware of his responsibilities. The will of John Edward Taylor, the younger son of the paper’s founder and the man from whom CP Scott bought it, urged that the Manchester Guardian should ‘be conducted in the future on the same lines and in the same spirit as heretofore’. John Scott’s father had achieved this and more besides. He felt a duty to do the same.

The solution to his problem was radical. In an act of extraordinary selflessness, he renounced all financial benefit in the business for himself and his family by transferring all the ordinary shares in the company – a stake worth more than £1 million at the time – to a group of trustees. The Scott Trust became the owner of the Manchester Guardian.

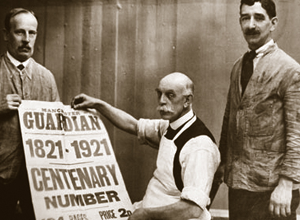

The Trust Deed of June 19, 1936 echoed the long-standing injunction to those who take up responsibility for the paper. It stated that the company must ‘be carried on as nearly as may be upon the same principles as they have heretofore been conducted’. This remains the sole instruction given to the incoming Guardian editor by the Trust.

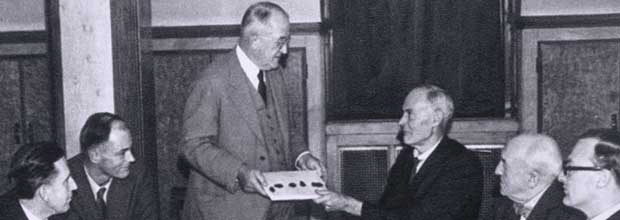

By 1948 there was concern that legal loopholes in the 1936 Trust Deed would allow the Inland Revenue to claim death duties when John Scott died. It was decided to reconstitute the Trust ‘in the spirit of the original agreement’ with new terms that would effectively protect the business from tax liability.

In November of that year the new members of the Trust were assembled in the Guardian’s offices on Cross Street. Five of them were beneficiaries of the 1936 Trust – four grandsons of CP Scott and the company secretary. They were each given a cheque for their share so that legally it became their personal property to do with what they wished – briefly making them millionaires in today’s terms. And then, one by one, they signed their fortunes away again and gave it all back to the Trust.

At this point the Scott family’s authority to appoint trustees was removed and the future maintenance of the Trust became a collective act.

The Trust operated under the 1948 Deed until its structure was reorganised in October 2008.

The creation of the Trust in 1936 removed the threat of death duties and protected the business from potential bankruptcy. But it was also an enormous personal sacrifice made in the public interest. Its ultimate purpose was to safeguard CP Scott’s legacy – the editorial freedom and liberal principles of the Manchester Guardian.

As current chair of the Trust Liz Forgan puts it, ‘The Trust owes its existence to an extraordinary act of philanthropy by the Scott family. It must be one of the great acts of generosity by any family in recent memory.’

This ‘extraordinary act of philanthropy’ resulted in a unique form of media ownership in the UK, which has now lasted more than 70 years.